The Friends of Universal Reform, about five hundred of them, trooped into Boston’s Chardon Street Chapel to debate the woman question, consider scriptural authority, and damn the institution of slavery. “A revolution of all Human affairs is now in progress,” Louisa May Alcott’s father, Bronson Alcott, happily declared. That was in 1840. The Unitarian minister George Ripley and his wife, Sophia Dana Ripley, were setting up a utopian community, Brook Farm, in West Roxbury, Massachusetts. “He who joins,” the artist Sarah Freeman Clarke said, “does it upon the principle of co-operation in labor and a desire for social improvement.” Margaret Fuller was already holding a series of “Conversations” for Boston women in a preview of the feminist movement. “One man renounces the use of animal food; and another of coin; and another of domestic hired service; and another of the State,” Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote to his friend Thomas Carlyle, “and on the whole we have a commendable share of reason and hope.”

America, it seems, has long been hospitable to hope, and sometimes even reason. Certainly this was true in Emerson’s day: consider abolition, the women’s rights movement, the Know Nothings, Young America, the Free Soil movement, temperance, the antivivisectionists, and then Populists and Greenbackers, to say nothing of transcendentalism.

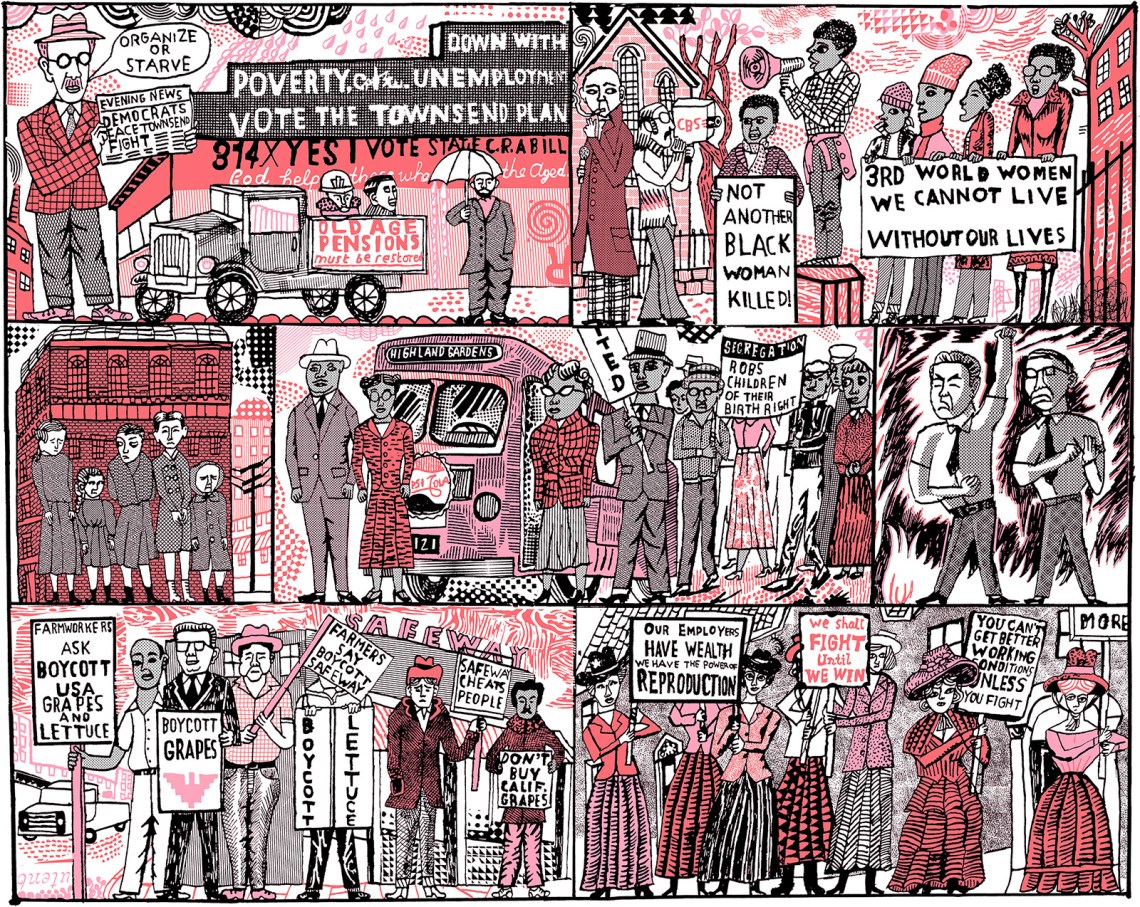

All these can be labeled social movements of one kind or another, and as Linda Gordon tells us in Seven Social Movements That Changed America, they “usually arise out of optimism.” An eminent academic historian and recently the author of The Second Coming of the KKK (2017), Gordon isn’t concerned here with the social movements of the nineteenth century but only those of the twentieth, which, she argues, “have been vital to progress in countless ways—from civil rights to Social Security, from support for the disabled to women’s rights, from freedom of speech to expanding higher education.” She adds, wisely, that not all social movements are salutary and cites examples from the twenty-first century like QAnon and MAGA.

By including a chapter (drawn from her earlier book) on the northern Ku Klux Klan, which she links to the fascist groups of the 1930s, she intends to “shed light on the threat from white nationalists today.” “As in all history writing,” she observes, “this study arose in the context of contemporary developments.” Mainly, though, she celebrates the other six social movements, which range from the settlement houses at the turn of the century to the second-wave feminism of the 1960s through the 1970s, any of which can become, she says, a “muscular supplement” to the act of voting. Social movements that grow less from grievances than disappointments—though certainly disappointment can shade into grievance—challenge conditions that seem insuperable, and by inspiring large groups of people, they ultimately beget voters.

This also seems true of movements not in her book: women’s suffrage in the early part of the twentieth century, the Harlem Renaissance, ACT UP, the Tea Party, environmentalism. And it would seem true of the progressive movement, which became the Progressive Party, and possibly William Bell Riley’s World Christian Fundamentals Association, which might also be considered a social movement. In fact, Gordon’s choice of just seven harbingers of change will inevitably invite objections: Where’s eugenics? The antinuclear movement? Creationism?

That is, her subject is a shaggy monster. Aware of this, Gordon sidesteps any rigid definition of a social movement, and though she doesn’t investigate their underlying similarities, she does list some of their salient features. Social movements create sociability. They provide a sense of community and solidarity, both formally and informally, even though their members may be angry. They require resources and physical spaces where people can come together. They often choreograph events and pageants or other entertainments and activities to keep their members involved. They can be tightly structured or not; they may have charismatic leaders or anonymous ones; they might be conservative or progressive; they may be inclusive, but most haven’t been. They’re generally nonviolent, the Ku Klux Klan of the South excluded. They’re usually short-lived but effective in the long term, for their legacies endure in one way or another. Though they are generally flawed (“How could they be otherwise?” Gordon asks), they often incur enough hostility, she remarks, to suggest that they have power. And, she meaningfully concludes, they often change “the universe of acceptable discourse.”

Obviously these movements can’t be separated from the myriad social problems that gave rise to them: industrialization, unemployment, unfair labor practices, racism, overcrowding, hunger, violence, sexism, and, of course, the Great Depression. Less concerned with dissecting these problems, Gordon is too savvy a historian to ignore the origins of the movements she examines—or to admire them unequivocally. Mostly, though, she salutes those with a grassroots organization that purports to challenge the status quo and that admits typically marginalized people, especially women.

Advertisement

Hull House in Chicago and the far less famous Phillis Wheatley Home in Cleveland provided immigrants from Europe and those Black men and women resettling in the North after Reconstruction with more than a community; these settlement houses provided a surrogate home. In fact, to Gordon, a place like Hull House, founded by Jane Addams, represents the “whole white settlement house movement.” It was a place where immigrants, mostly women, could find friends, work, educational opportunities, vocational training, literacy classes, and legal assistance. It even provided a day care center for children and eventually a gymnasium.

A response to the appalling living conditions endured by the working class and the poor, the settlement house movement had actually begun in England (Addams visited London’s Toynbee Hall several times), though, as the historian Daniel Rodgers notes, the American movement was more “deeply feminized” and thus more aware of the needs of families and neighborhoods. Yet Gordon reports with some disapproval that Hull House relied financially on the “privileged” women, worldly and educated, who possessed both the “elite connections” and sufficient “class confidence” to set it up in the first place. In other words, Hull House was both “a class and a racial project.” It was segregated; its summer camp admitted only whites. But it did create something worthwhile whose influence was lasting. The women of Hull House, like Addams and Florence Kelley, agitated for legislation regulating factory work, juvenile court systems, and improved sanitation; their commitment to social justice was real.

The same might be said of the Phillis Wheatley Home. Jane Edna Hunter, the daughter of South Carolina sharecroppers, arrived in Cleveland in 1905, but though a trained nurse, she was at first hired only to clean houses. And in this northern city, she also discovered what she called the “wholesale organized traffic in Black flesh”—i.e., prostitution—and aimed as a result to protect these young Black women who, like her, were alone in the city.

With support from white donors and then some Black leaders as well as from missionary societies, Hunter was able to raise enough money to open the Phillis Wheatley Home in 1911. It eventually consisted of a kitchen, a laundry, a dining room, and accommodations. By 1915 the eighty-nine young women living there could learn how to become well-starched domestic servants or seamstresses, cooks, and waitresses. Gordon points out that Hunter “shared the Cleveland’s Black elite’s assumption of the superiority of middle-class culture.”

Job training was important, but so was the “maternalism” that the Wheatley Home offered, which Gordon defines as a kind of protofeminism. For despite the apparent prudishness of Hunter’s often repressive regime as well as her acquiescence to the prejudice of her white donors, her decisions were often strategic, given the constraints of Jim Crow. Like the women of Hull House, Hunter wanted to promote the health and safety of the people she served. And, altogether, the settlement workers were sustained by a belief in progress and the notion that by mingling together in informal settings they would ameliorate hardship and inequity. By today’s standards, that might sound naive—even poignant.

Gordon turns from the settlement movement to the Ku Klux Klan, which, she writes, “imbricated itself into the American fabric” as a respectable organization exploiting the prejudice rife among white Protestants. She then suggests that the Klan morphed into the fascist alliances of the 1930s—the Silver and Black Legions, the German American Bund, the Christian Front (headed by the enormously popular and deeply bigoted Catholic priest Charles Coughlin), and various women’s groups, such as the Women’s National Association for the Preservation of the White Race. These all shared with the Klan what Gordon calls an “emotional infrastructure” largely based on paranoia and xenophobia.

A far less well-known movement of the 1930s was inspired by the gaunt self-styled guru Dr. Francis E. Townsend, who during the Depression proposed that retired citizens over the age of sixty be paid a monthly pension of $200, funded by sales taxes, which would free them from privation and fear. By putting more money into circulation and having more people able to spend it, he also hoped to stimulate a national economic recovery. Because the pension was to be offered to all retirees over sixty, it advanced “a democratic understanding of citizens’ entitlements,” Gordon writes, though its leaders “probably had little concern for elderly Black people or people of color in general.” Still, she is largely sympathetic toward the burgeoning movement, which soon included local dues-paying chapters with merchandise for sale, such as buttons, posters, and even busts of Dr. Townsend.

Gordon admits that the Townsend plan was impractical, unenforceable, and unrealistic. Its sales tax was regressive. Yet she argues that it helped inspire the passage of the Social Security Act of 1935 and create the “senior citizen” voting bloc. She even wonders if the lack of scholarship on this movement is a form of ageism, which it may well be. But it’s also true that arguments for old-age pensions, as they were called, existed before the restless and, according to Gordon, audacious and idealistic Townsend took the national stage. (As early as 1912, for instance, the Progressive Party platform included old-age pensions, and in 1930 New York representative Fiorello La Guardia argued for them in Congress.) Still, Gordon appreciates the movement’s ability to bring political pressure to bear on the government and thereby to make Social Security—and old age itself—acceptable. And though Townsend soon allied with Father Coughlin, she adds that in 1948 he supported the Progressive Henry Wallace for president.

Advertisement

Despite their flaws, Gordon is partial to the other left-leaning social movements of the 1930s that tackled unemployment, which she identifies in a thicket of acronyms. There’s the CP (Communist Party), the SP (Socialist Party), and the UCL (Unemployed Citizens’ League). This last is notable because it engaged in “prefigurative politics” (italics hers), which she defines as the effort “to be a microcosm of an ideal democratic society and economy.” That is, the organization, through its rules and procedures, embodied the ideal society it was trying to create. Even better, the group also aimed to be a “participatory democracy” (italics hers), meaning that every member shared in decision-making, and in the case of the UCL its “members rather than professionals were dispensing relief” so as not to embarrass or humiliate anyone who might need financial help. There was also the CPLA (Conference for Progressive Labor Action), organized by the orator Abraham Johannes Muste, which soon became the NUL (National Unemployed League) before it turned into the American Workers Party, which emphasized patriotism and “appealed to native-born whites with conservative race and gender values.”

These dissident groups, often quite critical of one another, derived their force, if not their existence, from the suffering, unemployment, and despair inflicted by the Great Depression and the collective sense that somehow American capitalism had failed. Regardless of how rigid or incoherent they might have been, or how competitive they were with one another, or their “gendered constraints,” without them, Gordon proposes, a number of social welfare programs would not exist. If they failed to effect “permanent social change,” it was because they were more concerned with tackling as quickly as possible the crises of the 1930s—unemployment, despondency, starvation. Moreover, these movements do not receive enough credit from historians, she claims, because politicians and policymakers have refused to acknowledge the impact they had on the national political culture. “To do so would only encourage them!” Gordon exclaims. Yet to Gordon, these movements did force the federal government to assume responsibility for the well-being of its citizens, particularly in relation to such social rights programs as Medicare and Medicaid.

Far more persuasive are Gordon’s analyses of the powerfully transformative movements of the second half of the twentieth century—the civil rights movement and the farmworkers’ and women’s movements. Though they’ve been amply dissected over the years by others, they provide Gordon with an opportunity to coin a new term, “followership,” so that she can pay homage to individuals whose impact has been obscured or overlooked. Often behind the scenes (particularly the women), they advise, they strategize, they arrange rides, they leaflet, they mimeograph, they raise cash, and they even cook to sustain a demonstration, or a boycott, or a cause. A case in point are the many people, again mostly women, involved in the successful Montgomery bus boycott of 1956, which brought an end to segregation in public transportation.

After Rosa Parks was arrested for refusing to give up her bus seat to a white person, the Montgomery Women’s Political Council mimeographed leaflets that at first called for a one-day boycott of city buses and united the Black population across class lines. E.D. Nixon, a Pullman porter and member of the important Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, then began to organize the local Montgomery clergy. He contacted the Reverend Ralph Abernathy, who backed the boycott. Abernathy reached out to the new pastor in town, Martin Luther King Jr. Together they formed the Montgomery Improvement Association, and the boycott took hold, fusing together a large community in a common cause despite the hardships it inevitably created. The working relationship among ministers, laity, bus riders, volunteers, activists, and the larger community defied prejudice, countenanced humiliation and jail, and finally emerged victorious when a federal district court ruled bus segregation unconstitutional—a ruling that the Supreme Court upheld.

Critical of the messianic and ultimately self-destructive policies of Cesar Chavez, Gordon nevertheless credits him as a brilliant tactician who campaigned tirelessly on behalf of Mexican farmworkers. By building a community organization (which included women but excluded Filipinos) and recruiting talented and self-confident leaders (Gordon discusses several of them in detail)—and in spite of the violence directed at them—Chavez was able to create a groundswell, and a union, the United Farm Workers, that wholly improved the lives of its members and their children. The grape boycott, which began in 1967, ultimately won farmworkers an eight-hour day, paid holidays, and contributions to the union’s medical and pension plans.

But it’s the women’s liberation movement that Gordon praises most fully and that she most intimately sketches, including criticism of its foibles and failures. She subtitles this final chapter of her book “Intersectionality in Practice.” Drawing on the term initially used in 1988 by the legal scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw, Gordon stresses how the interactions of racism, misogyny, and homophobia have shaped employment practices, free speech, public health, and even certain social movements. This, it appears, has been her book’s theme all along. For Gordon, the concept of “intersectionality” is one that “has traveled across the world” and best characterizes the progressive and admirable development of the women’s movement itself. That movement culminates, in her telling, in its persistent support of equal opportunity, reproductive rights, and environmental and social justice.

Observing that Francis Beal, a writer and activist initially associated with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, exposed within it “an interlocking system of discrimination, in an early suggestion of intersectionality,” Gordon then tracks the impact of the antiwar movement of the 1960s (“My generation was horrified and guilt-ridden” about Vietnam, she writes) to her own realization that a 1968 women’s conference was attended mainly by white women. (“Everyone felt guilty about it,” she recalls.) Though the motif here seems to be guilt, it’s also true that the women’s consciousness-raising discussions of the late 1960s and 1970s represented a kind of breakthrough for her. This method of “collective self-education,” as she calls it, “challenged classical liberal ideology about individualism.” Each self is part of a larger whole.

These individual groups appropriately came together in the organization known as Bread and Roses, which launched the Boston Women’s Health Book Collective. In 1970 it published the provocative, best-selling, and influential manual Our Bodies, Ourselves, focusing on women’s health and sexuality. A year later it sponsored the occupation of a building owned by Harvard as part of its campaign for a women’s center and affordable local housing for working people. And yet, Gordon notes, the overwhelming whiteness of the Bread and Rose membership continued to create within it even more “unresolved guilt feelings.”

Gordon’s survey thus ends with a paean to the National Black Feminist Organization, the “mother” of the Combahee River Collective, which developed “an intersectional analysis” of political power, imperialism, misogyny, racism, and class. Taking its name from the Combahee River raid of 1863, when Harriet Tubman and Black soldiers bravely liberated 750 enslaved people in South Carolina, the collective included among its members such activists as Barbara and Beverly Smith, Audre Lorde, and Chirlane McCray. An alternative to male-dominated organizations like the Black Panther Party and to groups composed mainly of white women, the collective was so deeply aware of the connections among sexuality, race, and class that it reached across boundaries, even national ones, to embrace all oppressed or disenfranchised peoples under its purview. The activist-scholar Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor wrote in a New Yorker essay, “Until Black Women Are Free, None of Us Will Be Free” (2020), that the Combahee River Collective “celebrated the possibilities of a political coalition born out of solidarity among groups who recognized the need to be engaged in struggle.”

The Combahee River Collective is a great place to end a book that commemorates social movements. Though Gordon insists that discussing their impact was never her aim, she concludes that public health legislation, old-age pensions and unemployment compensations, antisegregation laws, and the farmworkers’ union—all of them—augur the way social movements can create a democracy that’s more inclusive and participatory.

“A minority is powerless while it conforms to the majority,” Henry David Thoreau observed in Civil Disobedience, his protest against being taxed for a war he decidedly opposed, “but it is irresistible when it clogs by its whole weight.” This is what he called a “peaceable revolution” or, perhaps, a social movement—and maybe even an “intersectional” one. But he then added, in his typically acerbic style, “if any such is possible.” To Gordon, though, peaceable revolutions are not just possible; they are irresistible, they are powerful, they are born in hope and idealism, and they are maintained with courage and hard work, her discussions of the Klan and 1930s fascism notwithstanding. Warning that “we should not imagine that the United States is immune,” she reminds her readers—who, self-selecting, will need no reminding—that “racism, nationalism, violence and authoritarian leadership” retain some of their appeal. That, to me, in 2025, is quite an understatement.

Yet she steadfastly retains her optimism about social movements. These almost living creatures, as she aspirationally calls them, are vital and transformative partnerships that, by challenging the status quo, remain indispensable to the health of the nation. Or, as she declares, they make “American democracy democratic.”

If any such is possible.