Political repression is a matter of the Soviet past, according to Vladimir Putin. The human rights group Memorial disagrees. Although the Russian government disbanded Memorial’s Moscow-based Human Rights Center four years ago, the group’s project supporting political prisoners lives on, with almost all its staff now abroad.1 As of February 11, Memorial has officially recognized 837 political prisoners. Though over half of them are confined on the basis of religion, since Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, most arrests have been made for actions against the war. The month after the invasion, Russia added to its criminal code “discrediting” and “intentionally spreading false information” about the military. Speaking of executions in Bucha, for instance, became illegal.

To identify a detainee as a political prisoner, Memorial follows a rigorous process based on the definition used by the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe. A research team reviews each candidate’s case, including documents from court proceedings, then twelve board members deliberate. Anyone who has committed violence against another person that was not in self-defense, or has called for violence toward any group, is ineligible.

There are political prisoners whose cases go unrecognized. Last July, Pavel Kushnir, a pianist jailed for posting antiwar content on a YouTube channel with only five subscribers, died during a hunger strike while awaiting trial in Birobidzhan, near Russia’s border with China. Kushnir was not included in any organization’s count at the time. Memorial recognizes that its verified numbers are too low; the human rights monitoring group OVD-Info, which uses a less formal procedure to track politically motivated prosecutions more quickly, lists over three thousand people. Memorial estimates that the full number of political prisoners in Russian custody—including Ukrainian prisoners of war and civilian hostages in Russia and occupied territories, thought to total approximately 7,000 people—is probably around 10,000.

In August I spoke with Sergei Davidis, the director of Memorial’s Political Prisoners Support Program. He told me that since the invasion Russia is no longer “bothered by any legal niceties. It simply announces that whoever is against it is an enemy who has committed a crime.” (A few months after our conversation, the Russian state added Davidis, who lives in Vilnius, Lithuania, to its official list of terrorists without providing a reason.)

Memorial’s database shows the diverse forms that protest can take in a society that forbids any hint of dissent. A few of the prisoners it has listed are prominent, such as Alexey Navalny, who died in an Arctic penal colony last February, or the opposition politicians Ilya Yashin and Vladimir Kara-Murza, who were released in a multicountry prisoner swap in August. But many are barely known. Their stories reveal a hidden archipelago of opposition that has endured and adapted.

I learned from the database that in addition to regular mail (which tends to be slow and unreliable), some penal institutions offer an online service for correspondence with prisoners. For a small fee, letters are printed out, reviewed by a censor, and, if approved, handed to the prisoner, who can handwrite a reply that is in turn reviewed by the censor, scanned, and uploaded. The most used services, F-Pismo and Zonatelekom, are accessible only through local bank accounts, but another website, prisonmail.online/ru, takes foreign credit cards. I found contact information through Memorial, Telegram channels run by support groups, and Solidarity Zone, an organization that aids antiwar protesters accused of acts that might disqualify them from Memorial’s list (such as trying to derail trains).

Last summer I began writing letters to people imprisoned for resisting the war. I did not expect to hear back from them. A report by Amnesty International in June had described increasingly harsh censorship; its author was unable to communicate with anyone in prison. But, as one activist told me, “Listen, we live in Russia”—meaning that the state is not as ruthlessly efficient as it can seem. Decisions often depend on individual whim. One censor could allow a letter that condemns the government, while another rejects a postcard with turtles on it (true story). Mutual aid flows through the cracks.

To my surprise, nine of the fourteen prisoners I wrote to responded. Over the following months, six of them answered additional questions. I also conducted video and phone interviews with recently released prisoners and their family members, as well as volunteers, activists, and lawyers inside Russia. As I reached out to others, I began to understand why some were willing to talk despite the risks: they wanted witnesses.

Nikita Tushkanov is a thirty-year-old history teacher from a village that is entirely Komi, an indigenous group native to the northern Komi Republic. Some of his ancestors are ethnically Komi; others—like his great-grandfather—were sent to the region by force. In 1931, during Stalin’s drive to collectivize agriculture, Tushkanov’s great-grandfather was branded a kulak, or rich peasant, and deported from Luhansk (then Voroshilovgrad) to Komi, where he was forced to work as a logger. So was Tushkanov’s great-grandmother, a local whose neighbor accused her of stealing straw from the collective farm. Their son, Tushkanov’s grandfather, was sent to an orphanage at the age of six. “It was driven into my grandfather’s head that his parents were bad people,” Tushkanov wrote to me; his grandfather kept a portrait of Stalin on his wall until the mid-1990s.

Advertisement

Tushkanov grew up speaking the Finno-Ugric Komi language and learned Russian only at school. As a teenager, he began participating in efforts to recover the remains of Russian soldiers who had died fighting in World War II. “Thanks to these expeditions I understood that any war is just death, just tragedy, nothing more,” he said. In early 2021 he staged a one-man protest in support of Navalny, holding up a poster with the words “KEEP QUIET OR DIE” by the local Lenin statue. He was promptly fired from his teaching job for “immoral behavior.” Other schools in the area wouldn’t hire him, so he found work as a tutor.

In late 2022, Tushkanov was arrested for antiwar comments he had posted on the Russian social network VKontakte. (Among other things, he captioned a video of the Crimean Bridge explosion “A birthday gift for Putler.”) Federal Security Service (FSB) agents told him that in exchange for an apology, his sentence would be suspended and his prison term changed to house arrest. He refused. The court found him guilty of justifying terrorism and repeatedly discrediting the Russian military, placed him on the national list of terrorists and extremists, ordered him to pay a 150,000-ruble fine (about $1,500), and sentenced him to five years in a penal colony.

In 2023, Tushkanov married a Komi woman named Alexandra Kochanova, whom he had met after she read about his Navalny protest in the news and began following him on social media. They wed while he was being held in a remand center. She wore a white dress; he wore a T-shirt and sweatpants.

Tushkanov was given “strict conditions of confinement” that severely limit his contact with the outside world, including Kochanova. He is permitted three long and three short visits per year (which require prior approval) and is not allowed phone calls. Staff have repeatedly sent him to a punishment cell—where all correspondence is forbidden—for infractions like failing to greet a guard correctly or standing with his hands in his pockets.

“The hardest thing is the lack of direct contact with my loved ones,” he wrote me, “though I was born and grew up in a remote village in the taiga, and I often lived in the forest, so I’m used to rough conditions.” In a letter to his supporters on the first anniversary of his arrest, he said he had acted for the sake of his country, “which is mired in dirt and blood. And even if my actions pulled it out by a fraction of a millimeter, it is still important that I fought and am fighting.”

Dmitry Skurikhin, a fifty-year-old local opposition politician, lives in a village near St. Petersburg. In 2009 he began taping slogans like “I DON’T RECOGNIZE PUTIN AS THE PRESIDENT” on the side of his van. In 2014 he put up posters and graffiti condemning Russia’s annexation of Crimea on the walls of his general store. Over the next decade he displayed hundreds of anti-regime messages there, including ones in support of Navalny. In February 2023, on the first anniversary of the invasion, Skurikhin shared a photo online of himself kneeling in front of the store with a sign reading “FORGIVE US, UKRAINE.” He was arrested the following day. For his antiwar statements (including a poster that said “RUSSIAN SOCIETY, WAKE UP!”), he was found guilty of discrediting the Russian military and sentenced to a year and a half in a penal colony on the outskirts of St. Petersburg. The police stole his family’s savings—he is married with five children—when searching their house.

In the penal colony, Skurikhin had to clean toilets and shovel snow. To pass the time, he read sixty-one books, including ten volumes of Chekhov; he also learned Pushkin’s Eugene Onegin by heart. When we spoke over video chat in August, a few weeks after his release, Skurikhin described himself as “a foot soldier for democracy.” He believes that more Russians will eventually join his side: “I would like to think that we’re waking up, we’re waking up, and that we’ll come to the point where we’re not sleeping anymore.”

Ruslan Ushakov was born in 1993 in Cherkessk, a town in the North Caucasus, to a Chechen father and a Cherkess (or Circassian) mother. He moved to Moscow in his twenties. A true-crime aficionado, he launched a popular criminology Telegram channel and live-streamed lectures about serial killers on Twitch, making a living from viewer donations. Under a pseudonym, he also ran a separate Telegram chat with around nine hundred members, where he dissected murder cases and posted comments critical of the Russian authorities—above all, of the invasion of Ukraine. Ushakov wrote that “the destroyed maternity ward in Mariupol is a war crime that Russia and its residents will never be able to wash away.” “Both mother and child are dead,” he remarked after a Russian missile attack killed twenty-three civilians in the town of Vinnytsia. “Putin smiles: a little victory, but a victory all the same.”

Advertisement

In December 2022 masked armed men showed up at Ushakov’s apartment. They claimed to be from the gas company. After breaking down the door, they beat him for several hours, then tortured him with electric shocks in a police van until he confessed to idolizing Hitler and the Chechen guerrilla leader Shamil Basayev. He was convicted of calling for and justifying terrorism, rehabilitating Nazism, threatening to violently harm Russians, and spreading false information about the armed forces, including by criticizing the war in Chechnya. He is now serving an eight-year sentence in a penal colony in the Tver region, where he works six days a week in a garment factory (and tries to popularize veganism among the other prisoners).

Ushakov knew that he could be arrested for speaking out against the Russian state. All the same, he never imagined such a thing would happen to him: “I always told myself, ‘That’s paranoia,’ ‘Repressions won’t affect regular people,’ ‘There’s no point spending huge resources on going after internet dissidents.’… And here I am in prison.”

After the Russian government announced a “partial mobilization” in September 2022, which made hundreds of thousands more men eligible for conscription, dozens of people were arrested for attacking buildings associated with the military and security services, usually by throwing Molotov cocktails. Viktor,2 a language teacher in a provincial town, shot a bullet through a military recruitment billboard. The FSB tortured him, applying electric shocks to his body and putting a plastic bag over his head; they wanted him to confess to starting a fire at an enlistment office. He was also beaten in pretrial detention by prisoners who appeared to be acting on official orders. When he sought medical treatment, the doctor concluded that he had fallen on the street; the prosecutor declined to investigate.

After serving over two years in a penal colony, where he worked in a smelting plant, Viktor got out this summer. When we spoke over Telegram in August, he told me that shortly before his act of protest, he had finished playing Spec Ops: The Line—an antiwar video game loosely inspired by Apocalypse Now—which opened his eyes to “the horror of war.” Disturbed by the killings in Ukraine, he had a “meltdown” and decided to take matters into his own hands.

Since his release, he feels “paranoid, more suspicious,” he said. “I dream that they put me back in prison again, that I’m being tortured and cigarette butts are being put out on my body.” I asked him whether what he did was worth it. “Probably not,” he said, because of the financial and emotional costs to his loved ones.

As of last October, the independent Russian news site Mediazona had identified 137 people who have faced criminal charges for trying to sabotage Russian railways, often by diverting trains or setting signal boxes on fire. Most of them are young. A third of the accused are under eighteen, and almost two thirds are under twenty-four. Courts usually seal these cases from the public record, making information on them difficult to find.

A thirty-six-year-old anarchist named Ruslan Siddiqui carried out arguably the most daring attack of this kind. In November 2023 he was arrested for launching drone strikes on a Russian military airfield and blowing up railroad tracks used to supply troops. (Nineteen train cars were derailed, but no one was injured.) Siddiqui faces up to life in prison on charges including “undergoing training in terrorist activity.” The security services have told Russian media he was operating on the orders of Ukrainian intelligence. Siddiqui does not deny the attacks but told me he acted alone to save Ukrainian lives. Of all the letters I received from prisoners, only a message from him was partly redacted. The entire page describing his deeds was withheld, with a notification that it “did not pass the censor.” In another letter to me, however, he emphasized that he planned his actions to avoid casualties.

In the summer of 2022 one of the Ukrainian friends he had met on illegal backpacking trips to the Chornobyl exclusion zone was killed fighting in the Kharkiv region. “The grief of this loss” influenced his decision to act, he said. “I was ashamed that guys younger than me were dying, while I was in relative safety and doing nothing.” The final straw was the news that Russia was bombarding Ukraine’s power grid: “Since I was living with my grandmother, I understood just how vulnerable an old or sick person is if left without heat or light in the colder time of year.”

On January 31, 2024, in Moscow, Nadezhda Buyanova, a sixty-seven-year-old pediatrician, saw a seven-year-old patient who had a problem with his eye. His mother, Anastasia Akinshina, told Buyanova that the boy’s father, her ex-husband, had recently died in the war.

After leaving the clinic, Akinshina posted a video message about Buyanova in a pro-war Telegram channel. In the video Akinshina claimed that this “scum” had said that “killing our guys in the SVO [special military operation] is a legal action by Ukraine…. Does anyone have any idea where I should complain to get this bitch the hell out of here? Or even better, locked up?” (Buyanova says that Akinshina is mischaracterizing their conversation and that she did not mention Ukraine.) Akinshina also sent the video to another, larger channel connected to the security services, whose administrator posted it alongside a text stating that Buyanova had “mocked” a dead soldier, was from Ukraine, and “probably” gives money to the Ukrainian army.

The next day, plainclothes officers arrived at Buyanova’s clinic and interrogated her. She was immediately fired. The following evening police turned her apartment upside down and brought her in for an all-night interrogation. In an unusual move, Alexander Bastrykin, the head of the country’s main federal investigative authority, personally instructed a state prosecutor to charge her with spreading “false information” as well as being motivated by “national and political hatred.”

During her trial last fall, prosecutors cited Ukrainian-language video clips and holiday greetings found on Buyanova’s phone, as well as videos with Ukrainian titles she had liked on YouTube and chats in which she wished victory to Ukraine, as evidence of her guilt. In her final words to the court, she contested the notion that she had to decide between nationalities. Her mother was Belarusian, her father was Russian, and she was born and raised in Lviv. “What should I do?” she asked. “What choice should I make?” She was sentenced to five and a half years in prison.

In a letter she sent me from pretrial detention, Buyanova described her last days on the outside. She had felt a “premonition” that “prison was unavoidable”: “When I heard the beautiful sound of an accordion in an underpass, I walked out crying, stood there, listened, and told myself that I was saying farewell to my freedom.” She was “not angry” at Akinshina, she wrote. “Maybe, though not necessarily, she’ll come to understand what she has done.” Last spring someone sent Buyanova twenty kilograms of salt in order to exhaust her monthly limit for packages and prevent her from receiving anything else.

The Kremlin has forcibly closed many human rights organizations in Russia—including the Sakharov Center and the local offices of Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International, all of which shuttered after the 2022 invasion—under the “foreign agents” law. Yet local groups advocating for political prisoners still operate. Open Space, a collective based in Moscow and St. Petersburg, works with both political prisoners and their loved ones, offering free psychological, legal, and practical aid online and in person. At its physical locations, Open Space hosts events at which, for instance, people gather to write letters to prisoners.

The most devoted letter writer I’ve met is Anastasia,3 who chronicles her work with political prisoners on Telegram. She spoke to me by phone from a public bathroom in Moscow; when someone came in, she referred to “the war” as “the situation.” After the invasion she had struggled with a feeling of “helplessness,” she said. She watched an online lecture by the exiled political scientist Ekaterina Shulman, who recommended that Russians protest by writing to political prisoners, attending court hearings, and contacting legislators. Anastasia wasn’t interested in the latter—“I thought this was completely pointless”—but she started going to court and sending letters.

Anastasia now writes thirty to fifty letters a month. She also assembles packages, raises money, coordinates letter-writing evenings at Open Space, and sends even more letters online. According to the chart she keeps, she has written to 415 prisoners at least once. Her ex-husband disapproved of her activities: “He thought I was doing something wrong, illegal, that I’m a fool, that Americans had rotted my brain.” Her mother does not mention the stream of letters flowing in and out of Anastasia’s apartment when she comes to visit.

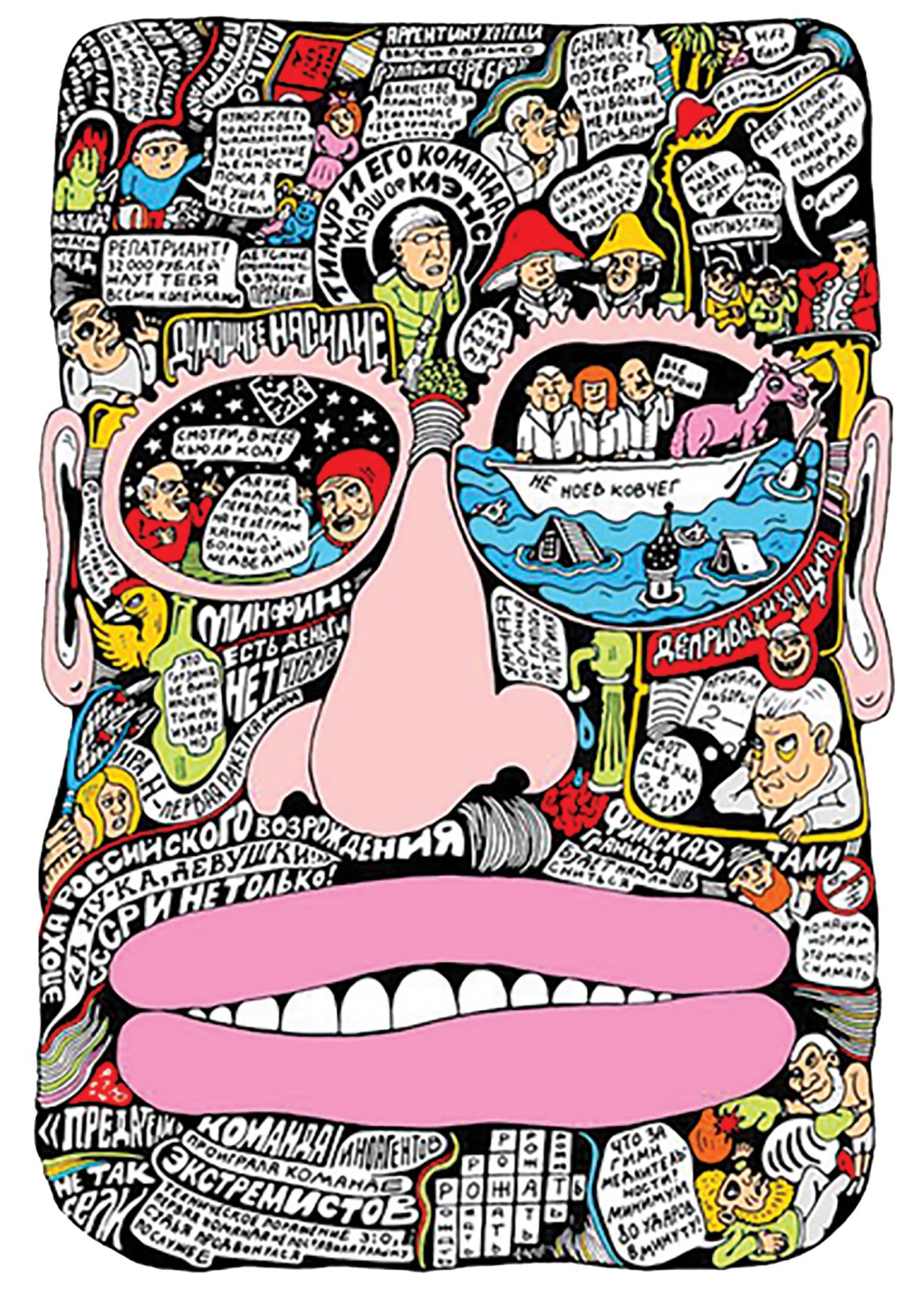

Peter Losev is an organizer in Moscow who used to run campaigns for opposition politicians. In early 2022 his friend Daniel Kholodny, a Navalny associate, was jailed—but the public outcry was short-lived. “A person was arrested, he was written about, and then the next day everyone forgot,” Losev said. To help political prisoners like Kholodny feel less “abandoned,” he established a samizdat monthly, Tiuremnyi vestnik (the Prison Herald), whose small editorial team provides sardonic updates on domestic and international news. A cartoon on the cover of a recent issue depicts devastating flooding in parts of Siberia and the Urals, where residents were largely left to fend for themselves. Oblivious bureaucrats in white suits, accompanied by a unicorn, hold a sign saying “EVERYTHING IS FINE” aboard a ship labeled “NOT NOAH’S ARK.” (Nearby, wooden houses and a church sink underwater.)

At its peak, the Herald went out to around three hundred prisoners. Now it is sent to about 150, but penal institutions destroy most copies. When Losev learned about this, he created a legal project named Freedom of Correspondence (FOC), which sues prisons for withholding inmates’ mail. It currently has three cases underway. The lawyers must be cautious: in a previous case, when the judge seemed poised to rule in the prisoner’s favor, the penal colony’s administration moved him to a punishment cell. Eventually, Losev said, the parties came to a “gentleman’s agreement”: the suit was withdrawn on the understanding that FOC would stop suing the prison, and “they will not censor what should not be censored.” In another case, which Losev believes FOC would have won, the legal team settled out of court, fearing retaliation.

A lawyer who works with FOC explained to me why prisons sometimes make a deal. If the institution loses a suit, any financial penalty is deducted from its budget, and a note is added to the files of the relevant employees, which could prevent their promotion. The lawyer believes that FOC’s legal efforts, however slow and arduous, are valuable for exposing the system’s hidden workings. He said he fights for political prisoners’ rights because “I was taught in my family that you should love your motherland, and that the motherland and the government are not synonymous.”

Once they’ve served their sentences, political prisoners reenter a society that demands silence in exchange for freedom. Criminal charges are not the only means of enforcing conformity; some who have criticized the war have lost jobs or been ostracized by their communities. A member of Open Space described to me how the police sometimes invite people to come to the station for a “prophylactic chat,” which is voluntary but signals that they are being watched. In the face of legal and social pressure, open dissent has all but vanished.

No one knows what exactly is safe. Though Telegram is widely used in Russia, cybersecurity experts have argued that its owners cooperate with the authorities. (In late September 2024, Telegram’s founder and CEO, Pavel Durov, announced that to “discourage criminals,” the app would begin turning over users’ IP addresses and phone numbers in response to “valid” legal requests. He had previously assured users that their privacy was “sacred.”) On the day of the invasion, Marina Matsapulina and several other opposition politicians requested official permission to hold an antiwar demonstration. The request was denied; Matsapulina was arrested and interrogated, then released. A few weeks later, after moving to Armenia, she wrote a Twitter thread describing how a Ministry of Internal Affairs officer had quoted, word for word, messages that she had sent to her friends on Telegram. Other users have reported strange activity that suggests their accounts are compromised, even in supposedly encrypted chats. In early September, when I was checking quotes and facts with sources for this article, my account was banned. When I reestablished contact with one source, he told me that all my messages had disappeared.

For those in confinement, a strange sort of freedom can come from refusing to back down. In 2023, Lyudmila Razumova, a fifty-seven-year-old artist who lives in the Tver region, received a seven-and-a-half-year sentence (along with her then husband, Alexander Martynov) for opposing the war on social media and stenciling slogans like “UKRAINE, FORGIVE US” on the side of a village store. In a letter to one of her supporters, she admitted that she hadn’t been interested in politics until the invasion. She has since come to feel that “all our troubles arose precisely because everyone thought this way, except for the ones who were more honest, more honest and stronger, than those of us who meekly stayed silent.”

FOC has filed a lawsuit against Razumova’s penal colony for intercepting her copy of the Prison Herald as well as numerous letters. I listened to a recording of a recent court hearing at which she appeared by video link. Razumova said she was tired and asked to sit down—she works in a prison sewing factory—but the judge insisted she stand. When Razumova had trouble hearing because of a bad microphone, the judge reprimanded her for not showing sufficient respect. The judge then said that the Herald had been declared “undesirable.”

“I don’t understand what ‘undesirable’ means,” Razumova replied. “Undesirable for whom? It’s very desired by me.”

The judge asked what crime she was convicted of.

“In my opinion, there was no crime,” she said, but explained the charges of spreading false information about the Russian armed forces.

“That’s not a crime?”

“No, I spread the truth.”

—February 12, 2025

This Issue

March 13, 2025

From Comedy to Brutality

Selling Out Our Public Schools

-

1

Memorial HRC was closed under Russia’s “foreign agents” law (passed in 2012 and subsequently expanded), which requires organizations and individuals labeled as being under “foreign influence” to register as “foreign agents” and comply with onerous regulations. Violations can lead to heavy financial penalties and criminal prosecution. ↩

-

2

His name has been changed. ↩

-

3

Her last name has been withheld. ↩